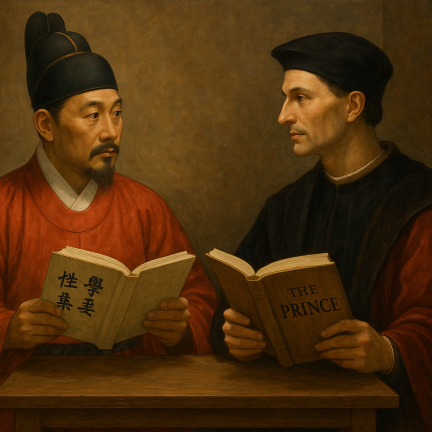

Two influential political treatises have shaped the philosophies of governance in East and West: The Essentials of Governing the People through the Study of the Sage (Seonghakjipyo), written by Korean Confucian scholar Yi I in the mid-Joseon period, and The Prince by Italian Renaissance thinker Niccolò Machiavelli. Despite emerging from different cultural and historical contexts, both books raise the same fundamental question: “What makes good governance?” While Yi I emphasizes moral virtue rooted in Confucian ideals, Machiavelli underscores the importance of political realism and power strategy. Each work provides profound insights into the ideal qualities of leadership and the philosophy of rule.

Seonghakjipyo: A Confucian Manual for Cultivating a Sage Monarch

Yi I’s Seonghakjipyo, written in 1574 and presented to King Seonjo, is a political primer grounded in Neo-Confucian morality. Its central thesis revolves around the Confucian principle of sugi chiin (修己治人), or “cultivating oneself to govern others.” Yi insists that the foundation of politics must begin with the ruler’s self-discipline, arguing that inner moral development must align with outward political action.

Divided into six sections, Seonghakjipyo draws upon Zhu Xi’s Neo-Confucianism and Confucius’ ethical teachings. Yi stresses the doctrine of rule by virtue (deokchi), asserting that political power is a mandate from Heaven and must be exercised through wisdom and personal integrity. Essential virtues for a monarch include practicing reverence (gyeong), appointing righteous ministers, and nurturing the people with parental compassion.

Yi particularly emphasized how even a monarch’s smallest behavior could deeply impact the people. A careless act could shake public confidence or erode social morals. Hence, Seonghakjipyo is not just a manual of governance but a treatise on leadership grounded in ethics and human nature. The ideal ruler, according to Yi, must be a moral exemplar—an idea that still resonates in modern leadership discourse.

The Prince: A Ruthless Manual for Realpolitik

In stark contrast, Machiavelli’s The Prince, written in 1513, is a pragmatic guide to maintaining power amidst the chaos of Renaissance Italy. Famous for its assertion that “the ends justify the means,” the book argues that a ruler should prioritize political survival and state stability—even at the expense of traditional morality.

Machiavelli viewed human nature as inherently selfish and fickle. To govern effectively, a prince must possess the strength of a lion and the cunning of a fox. Unlike Confucian virtue, Machiavelli champions political expediency and results over moral principles. His ideal leader is a realist who navigates power dynamics with tactical savvy, not idealistic virtue.

His political philosophy emerged in response to Italy’s fragmented and unstable political landscape. With power constantly shifting and foreign forces intervening, Machiavelli sought practical solutions for national unification and strong government. He advocated for fear over love in maintaining authority and urged political decisions to be free from religious or moral restraints. In this regard, The Prince laid the groundwork for modern political science.

Virtue and Pragmatism: Contradiction or Complement?

At first glance, Seonghakjipyo and The Prince seem diametrically opposed. The former emphasizes moral cultivation and divine mandate; the latter stresses power retention and human nature’s darker truths. Yet both grapple with the same question: “What is the ruler’s responsibility?”

Yi’s vision of virtuous governance rests on ethical introspection and benevolence to the people, while Machiavelli’s realism stems from the brutal political turmoil of his time. One is idealistic, the other pragmatic. Nevertheless, both are deeply relevant even in modern democracies. Political leaders today must constantly navigate the tension between ethical ideals and practical necessities—making these works timeless references for understanding power and leadership.

Moreover, these texts offer contrasting but enriching perspectives on leadership. Today’s corporate CEOs and public administrators also wrestle with the trade-offs between ethical legitimacy and performance. In result-driven organizations, Machiavellian tactics might offer short-term success, but Confucian principles often foster long-term trust and organizational cohesion.

From an educational standpoint, both books serve as invaluable resources. Seonghakjipyo provides a framework for moral character and ethical education, while The Prince sharpens critical thinking and political awareness. Studying them in tandem equips future leaders and students with a more balanced, multidimensional understanding of governance.

Conclusion: Enduring Mirrors for Leadership

Seonghakjipyo and The Prince are more than relics of bygone eras—they remain vital inquiries into the character and responsibility of leadership. Yi I promoted moral integrity and personal cultivation as the foundation of rulership, while Machiavelli offered a stark reflection of political survival and power dynamics. Each, in their own way, asks: “What makes a good ruler?”

In a world still rife with political complexity, today’s leaders can find wisdom in both traditions. Striking a balance between idealism and realism, between ethics and power, remains the central challenge of governance. Virtue and pragmatism are not mutually exclusive; when harmonized, they form a richer philosophy of leadership—one that continues to illuminate the path forward.